As you think about which goals to pursue in the new year, consider one with lasting impact: building a legacy.

“What do I want to leave the world? How do I want to be remembered?” said Lisa Marchiano, a psychotherapist in Philadelphia. “When we think in terms of legacy, we’re really trying to use our imagination to think far beyond our own individual existence.”

Short-term goals such as starting a new hobby or saving money for a special vacation can be valuable, but a legacy mind-set requires different considerations. Building a legacy — which benefits others and will survive beyond your lifetime — encourages you to think deeper and longer term, experts say.

How to start building a legacy

Legacy building does not have to be a grand project; it can be a simple one that speaks to your strengths and values. Some examples:

- Start a collection of recipes of favorite family dishes to give to younger relatives.

- Support an organization that does vital work.

- Mentor a youth who needs guidance and a mature perspective.

- Leave your life lessons in story form for your loved ones or community.

- Create scrapbooks and photo albums, clearly labeled with added written accounts, so memories won’t be forgotten.

- Research your ancestry and create a family tree.

- Use your talents to create a new family heirloom, for example, a wood sculpture or furniture, a painting or a piece of pottery.

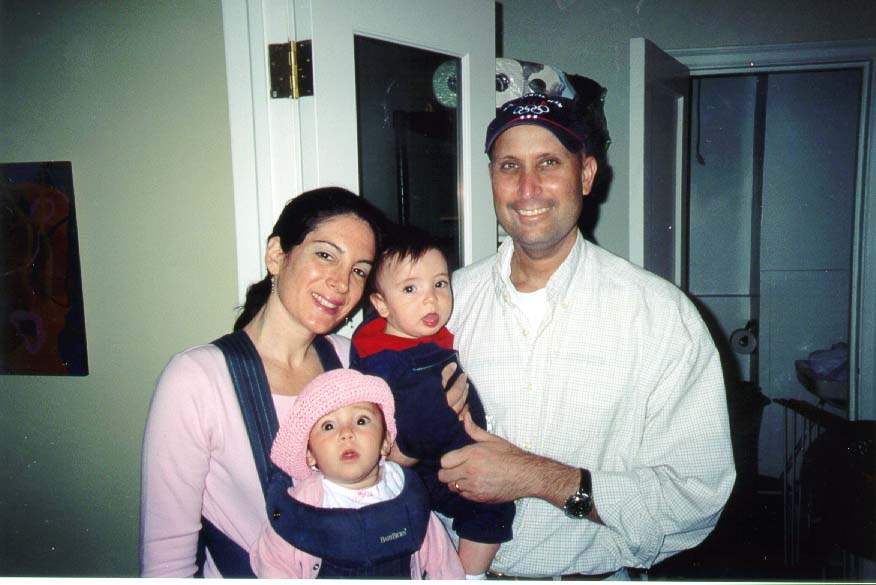

Howard Kaplan, a financial adviser in Cincinnati, comes from a tight-knit family, a legacy, he says, he inherited from a maternal grandmother who prized extended kin gatherings.

As part of his own legacy, Kaplan, 56, wrote a digital document he called a ‘life letter’ for his daughters, Hannah, 25, and Sarah, 22.

Reflecting on his own values, goals and life lessons benefited him, too, he said: “It was a gift for myself.”

“I wanted to tell my story,” Kaplan said, to let family and descendants know “why I made certain decisions and how I became who I am.” His family is close, but he had not expressed his thoughts to them in such a way, he said.

Among the top lessons for his offspring: Life is hard. “Not that that’s bad. It’s just the way it is,” he said. “There is no easy bus that’s coming for us, so we’re all going to have to work hard.”

But he was also creative and playful. Kaplan loves music, he said, from Beethoven to AC/DC. He paired his life letter to his daughters with a playlist of 42 songs that hold meaning for him. His favorite: “Family Affair” by Mary J. Blige. “The beat is amazing,” he said, but he’s also drawn to the lyrics: “We don’t need no haters. We’re just trying to love one another.”

|

You don’t need to have children to embrace a legacy resolution. For example, you can support or volunteer at an organization, including one that might outlive you.

Charming Evelyn, 56, grew up in the Caribbean, where conservation was a way of life. Households, including hers, collected rainwater in large storage tanks for domestic use, she said.

“We do not waste,” she said. People reused plastic containers and turned empty cookie tins into sewing boxes. “There was already a level of recycling happening,” she said.

Evelyn parlayed that tradition of conservation and a love of nature into a long-standing volunteer commitment with the Sierra Club, a grass-roots environmental organization. She volunteers as the chair of the water committee for the Sierra Club Angeles Chapter and has worked on issues such as water conservation and depletion of groundwater.

Evelyn hopes her efforts will have long-lasting effects. She asks herself, “How am I leaving the earth? What is my impact for future generations?”

People have asked why she engages in environmental causes when she has no children, she said. “I may not have kids, but I have friends who have kids,” she said. Evelyn has also spoken to youth about her work, she said, and if it encourages them to participate in the environmental movement, “I shall be vastly satisfied.”

“The idea of legacy — what we’re going to leave behind us — is really related to the issue of meaning,” Marchiano said. “A lot of the malaise in the modern person — the things that bring people into my office, for example — are related to a lack of a sense of meaning and purpose.”

With meaning and purpose, “there’s more contentment in life,” she said.

Don’t wait to leave a legacy

Kaplan surprised his daughters with his life letter shortly after he wrote it. “I’m not a touchy-feely person, typically,” so his daughters were “shocked,” but appreciated his openness, he said.

Don’t wait to pass down a legacy, said Nancy Sharp, an author and story coach in Denver. She guided Kaplan in creating his life letter, which some people also call an ethical will. These aren’t legal documents, but rather, a snapshot document to capture one’s essence through the recollection of meaningful experiences, key family history, values, life lessons, and hopes and wishes for future generations.

“Ideally, this should be shared during one’s lifetime,” Sharp said.

Younger people can write ethical wills and life letters, too.

“You know, life happens,” Sharp said. In 2001, on the same day that her twins Rebecca and Casey were born, she and her then-husband Brett Zickerman learned that his brain cancer had returned. A couple of years later, he died at 39, leaving her a 37-year-old widow with two toddlers.

During his illness, the couple felt too overwhelmed to ponder Brett’s leaving a legacy for his children, Sharp said, which created a void. In hindsight, she said, a life letter would have been a treasure for their twins, now 22. “I feel that the gift of Brett’s words in a beautiful document would have been the most enduring gift of all,” she said.

Since then, Sharp, who has remarried, has coached Kaplan and many other clients in writing life letters. As part of a legacy resolution, start a life letter with a couple of pages, then keep updating it, she said. “Your story is still being written,” she said.

To create any kind of legacy resolution, “It goes to a question of values. What really matters to you?” Marchiano said. “And then you could ask yourself, ‘What would I like my legacy to be in that area?’ ”

“When we look at the night sky, we have an experience of awe because we see how infinitely small we are in such a huge world,” she said. Something similar happens when we think about a legacy, Marchiano said.

We must remember that “our existence is really a pretty small blip that’s going to occur between our ancestors and those who come after us,” she said. A legacy “inspires a broader view that is humbling, but opens us up to a much larger way of looking at the world and ourselves.”