For more almost 5 decades, funeral director Harry Greer, 74, has ushered families through loss and grief in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Alameda. But the coronavirus pandemic has roiled his business. Recently, two families postponed funerals until May. Then this week, a third family cancelled at the last minute, the funeral only days away.

The reason? On Monday, March 16, Alamedans received a startling notice on their cell phones. In a bid to slow the spread of coronavirus, the 78,000 residents of this island city were ordered to shelter in place beginning at midnight, March 17. Local public health departments in seven Bay Area counties, including San Francisco and Alameda Counties, ordered 7 million residents to stay in their homes until April 7, leaving only for essential outings, such as buying groceries or getting prescriptions or medical care.

Governments, first responders and utilities would still function, but people could only go to work at essential businesses, among them, health care, food supplies, banks and gas stations. The San Francisco Bay Area was the first region in the nation to impose such a sweeping shelter order.

Daily life changed overnight. In Greer’s line of work, it matters to provide clients with a compassionate human touch. When a loved one dies, family and friends congregate to mourn and to remember collectively. “People need support,” Greer says, “and they get it from others.” But coronavirus, which has dominated headlines for months with images of fear, sickness and death, has forced people to grieve apart. Some have turned to online services or limited gatherings to 10 people, as the White House has advised. In fact, Greer, the owner of Alameda Funeral and Cremation Services, will soon have a church service for 10 people, followed by a cemetery burial with the same restriction.

The crisis has also prompted Greer to change his work style. He’ll continue to help people with funeral arrangements through phone calls, faxes and emails, but meet in person only to sign documents. He knows that the change will be hard for some clients, but he does plan to keep his business going. “When somebody dies, somebody’s got to take care of them,” he says.

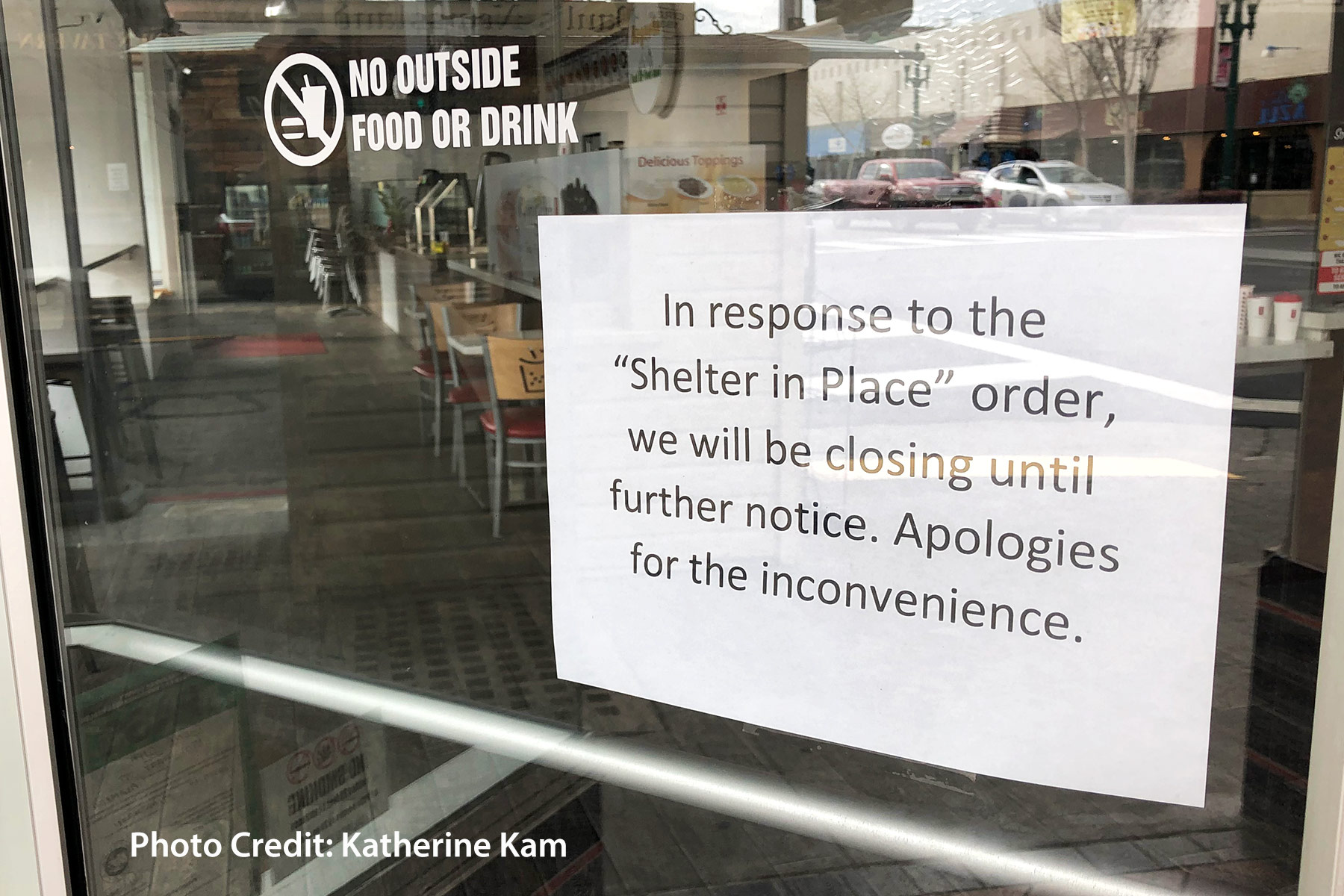

Besides funerals, weddings have also been postponed. Local church services have gone online only. Alameda’s three libraries have closed, and City Hall is shuttered to the public until early April. The shelter order mandates that restaurants close their dining rooms and offer takeout and delivery only.

The order has capped a tumultuous week for this city located between San Francisco and Oakland. Alamedans prize the relaxed, friendly atmosphere. Many turn out regularly for the city’s annual Fourth of July parade. They consider their town down-to-earth compared to San Francisco, its renowned neighbor across the bay.

Spiking cases required action

In Alameda, though, one can find examples of changes happening throughout the region. The specter of coronavirus has hung in the air for weeks, with the first Bay Area case of COVID-19 discovered on January 31. The most cases are in Santa Clara County, with 175 cases and 6 deaths. Altogether, the Bay Area accounts for about 46% of the cases in California.

In Alameda County, where the town of Alameda lies, there have been 31 confirmed cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus. San Francisco, whose skyline can be seen from Alameda’s bayfront shoreline on a clear day, has seen its streets emptied of tourists and workers. It has 51 cases.

For Alameda residents, the big headlines came closer to home when the Grand Princess cruise ship began unloading passengers on March 9, some diagnosed with COVID-19. They disembarked at the Port of Oakland, just across the estuary from Alameda.

Coronavirus has hit Alameda in other publicized ways. After an Alameda firefighter became infected, eight more firefighters were quarantined.

Schools, shops forced to close

Alameda High, housed downtown in a historic building with Grecian columns sweeping across the front, stood empty on a school day when it’s usually mobbed with students.

The Alameda Unified School District, which serves 9,500 students, closed all campuses from March 16 to April 3 after holding an emergency meeting. Its public notice cited “the high levels of anxiety we are witnessing in our community and the sheer amount of uncertainty on what we can expect with this public health situation.” In closing its schools, Alameda has joined many other cities throughout the state, including the public school systems in San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles.

Shirley Tong, an accountant, has three young children living at home. Before the school closing, she was worried enough to talk with other parents about whether they should keep their kids off campus. The school district had decided to leave the doors open, but encouraged families to keep students at home if possible. She and the other parents agreed that they would pull their kids out, Tong says.

Then she got notice from the school district announcing the full closure. Among her social circles, there’s relief and no more guesswork. “Everyone’s happy about the school district decision,” she says. “The major reason is, you’re not waiting for something to happen and then close the schools. You’d rather prevent it.”

Her office is in nearby Oakland, and she was concerned about her work schedule. Although her life has become more complicated, her husband works from home. “We can manage it,” she says. “We knew this was going to happen.”

Her children understand why they can no longer tag along on family trips to the crowded Costco, she says. “We don’t want to take any chances.”

On March 13, the day that the school district announced the closure, President Donald Trump also declared a national emergency. Parents flooded the stores to stock up on food. One woman stared at the long lines while holding a tub of ice cream. “My kids are home for three weeks, so I’m going to throw junk food at them,” she says.

A run on grocery stores

At many of Alameda’s stores, customers could find no toilet paper, nor could clerks tell them when new shipments would come in. One store had an empty seafood case and a bread section that was almost bare.

The local Trader Joe’s was so overwhelmed that it began limiting customers, workers checking that the store was not too crowded before letting more people in. A store employee explained that there were too many people and that products were running low on some shelves. By controlling the crowds, “It’s not as frantic,” he says. “It creates a better shopping experience. Everyone has a little more space and people can get what they want.”

A CVS pharmacy in town was less crowded. A sign at the pharmacist’s counter stated that there was no more hand sanitizer, rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide and masks. Some customers stood 6 feet behind the person in front of them. The pharmacist on duty was asking people to consider scheduling home delivery to avoid coming into the store.

Alameda teens accustomed to hanging out together all over town have had to build distance into their lives, too.

At first, Miranda Mitchell, 14, an Alameda High ninth-grader, was glad–along with her friends—at the prospect of schools closing. “Originally, we were happy because we didn’t want to go to school. We didn’t realize how serious it was,” she says.

Now, she’s at home, doing schoolwork online. Her dance classes have been cancelled, and her piano and voice teachers have switched from in-person to virtual lessons. Until the shelter-in-place order, she was able to hang out with her friends at each other’s homes. “Now, my parents aren’t letting me,” she says. Instead, she texts with friends every day.

Her father, Bruce, 50, a mechanic with United Airlines, still commutes to work at San Francisco International Airport. But he’s worried about layoffs now that the airlines are in trouble, with so many people refusing to fly.

Miranda’s mother, Karen, 55, a media buyer and content writer in Oakland, was instructed to work from home as her office closed. Her bosses had been giving employees the choice to work remotely, but she was grateful when they made a final decision to send everyone home, she says. “It’s almost easier when someone says, ‘This is the way we’re doing it.’”

She’s made other changes on her own. She quit her gym because it often ran out of hand sanitizer and paper towels. “It kind of makes me sad, but I didn’t feel they were keeping up their cleanliness.”

She’s also stopped going to a larger supermarket in favor of a smaller, less crowded grocery store. And even before the shelter order, she had decided not to attend parties with friends. She’s hunkering down because she supports the shelter-in-place order.

Among her circles, not everyone takes the threat seriously, she says. “They think the media’s over-reacting, there’s not that high a death rate—I feel they’re really in denial.”

Unusual becoming normal

By the second day, though, the mandate seemed to have taken hold. The downtown sidewalks were mostly deserted, except for a few people getting off the bus, walking their dogs or picking up takeout food. Going out to walk, bike or exercise is allowed, as long as people stay 6 feet away from others. But no gathering in groups is allowed.

An office supply store remained open to enable people to work from home. But hair salons, department stores and martial arts studios have gone dark. While many eateries have remained open for takeout, others have chosen to close.

Although Greer, the funeral director, considers the shelter order to be wise, he worries about so many businesses taking a hit. “People need to pay the bills,” he says.

The grocery stores were still doing brisk business, though. At Trader Joe’s, people were still lining up to get inside, but after the order, they kept 6 feet apart, some wearing masks.

High school senior proms and sports meets have been cancelled, and perhaps graduations, too. It’s not clear whether crowds of residents will be able to line the sidewalks for the Fourth of July parade.

For now, the Mitchells have had to cancel an upcoming celebration for their daughter. The shelter-in-place order came down only a few days before Miranda’s planned 15th birthday party. She had invited more than a dozen classmates for a backyard gathering, she says. “We were going to have a projector to project a movie onto the fence and order pizza.” With the situation so uncertain, she doesn’t know when she’ll be able to have the gathering. “When it gets better,” she says.

Recently, she was talking with her voice teacher, a woman in her thirties, about coronavirus. The teacher told her, “It’s really crazy that you are living through this in your childhood because in the past 100 years, no one has really lived through anything like this as a child,” Miranda says.

The young teen didn’t understand the context, didn’t realize that coronavirus was posing such a health crisis. But she’s starting to grasp the seriousness. “I thought we would just get school off and that was it. I didn’t realize it would go this far,” she says.

“I’m looking forward to when everything will go back to normal.”